MTC: Lawyers and AI Oversight: What the VA’s Patient Safety Warning Teaches About Ethical Law Firm Technology Use! ⚖️🤖

/Human-in-the-loop is the point: Effective oversight happens where AI meets care—aligning clinical judgment, privacy, and compliance with real-world workflows.

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ experience with generative AI is not a distant government problem; it is a mirror held up to every law firm experimenting with AI tools for drafting, research, and client communication. I recently listened to an interview by Terry Gerton of the Federal News Network of Charyl Mason, Inspector General of the Department of Veterans Affairs, “VA rolled out new AI tools quickly, but without a system to catch mistakes, patient safety is on the line” and gained some insights on how lawyers can learn from this perhaps hastilly impliment AI program. VA clinicians are using AI chatbots to document visits and support clinical decisions, yet a federal watchdog has warned that there is no formal mechanism to identify, track, or resolve AI‑related risks—a “potential patient safety risk” created by speed without governance. In law, that same pattern translates into “potential client safety and justice risk,” because the core failure is identical: deploying powerful systems without a structured way to catch and correct their mistakes.

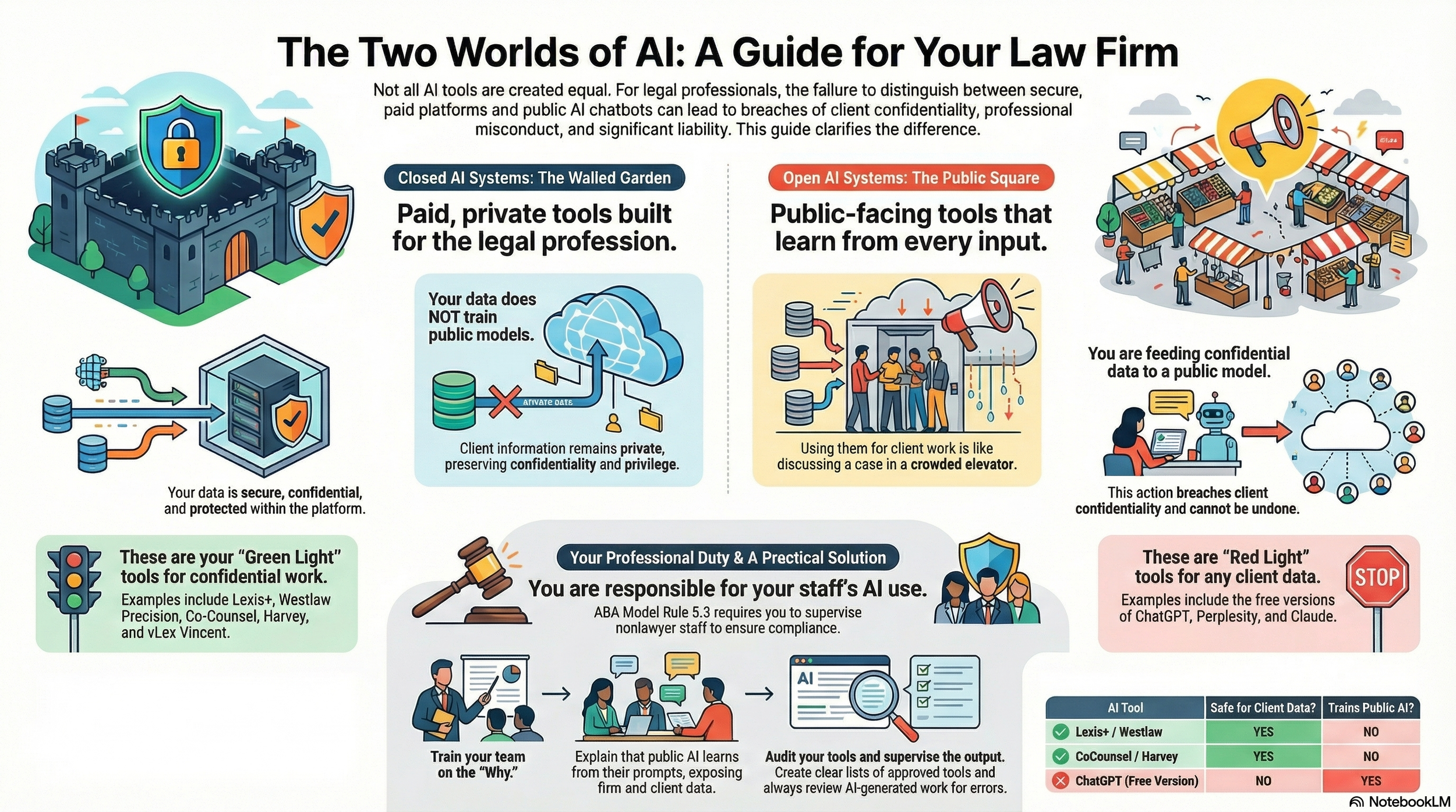

The oversight gap at the VA is striking. There is no standardized process for reporting AI‑related concerns, no feedback loop to detect patterns, and no clearly assigned responsibility for coordinating safety responses across the organization. Clinicians may have helpful tools, but the institution lacks the governance architecture that turns “helpful” into “reliably safe.” When law firms license AI research platforms, enable generative tools in email and document systems, or encourage staff to “try out” chatbots on live matters without written policies, risk registers, or escalation paths, they recreate that same governance vacuum. If no one measures hallucinations, data leakage, or embedded bias in outputs, risk management has given way to wishful thinking.

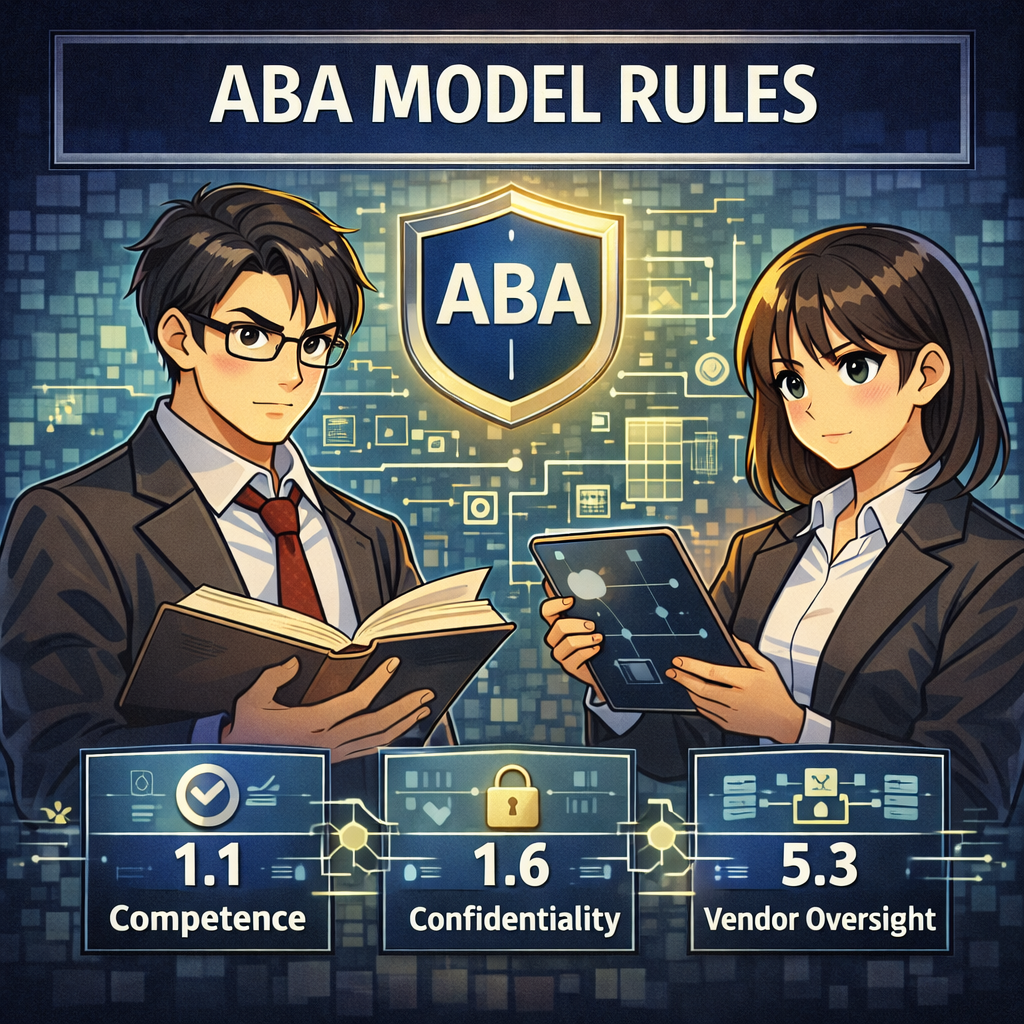

Existing ethics rules already tell us why that is unacceptable. Under ABA Model Rule 1.1, competence now includes understanding the capabilities and limitations of AI tools used in practice, or associating with someone who does. Model Rule 1.6 requires lawyers to critically evaluate what client information is fed into self‑learning systems and whether informed consent is required, particularly when providers reuse inputs for training. Model Rules 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3 extend these obligations across partners, supervising lawyers, and non‑lawyer staff: if a supervised lawyer or paraprofessional relies on AI in a way that undermines client protection, firm leadership cannot plausibly claim ignorance. And rules on candor to tribunals make clear that “the AI drafted it” is never a defense to filing inaccurate or fictitious authority.

Explaining the algorithm to decision-makers: Oversight means making AI risks understandable to judges, boards, and the public—clearly and credibly.

What the VA story adds is a vivid reminder that effective AI oversight is a system, not a slogan. The inspector general emphasized that AI can be “a helpful tool” only if it is paired with meaningful human engagement: defined review processes, clear routes for reporting concerns, and institutional learning from near misses. For law practice, that points directly toward structured workflows. AI‑assisted drafts should be treated as hypotheses, not answers. Reasonable human oversight includes verifying citations, checking quotations against original sources, stress‑testing legal conclusions, and documenting that review—especially in high‑stakes matters involving liberty, benefits, regulatory exposure, or professional discipline.

For lawyers with limited to moderate tech skills, this should not be discouraging; done correctly, AI governance actually makes technology more approachable. You do not need to understand model weights or training architectures to ask practical questions: What data does this tool see? When has it been wrong in the past? Who is responsible for catching those errors before they reach a client, a court, or an opposing party? Thoughtful prompts, standardized checklists for reviewing AI output, and clear sign‑off requirements are all well within reach of every practitioner.

The VA’s experience also highlights the importance of mapping AI uses and classifying their risk. In health care, certain AI use cases are obviously safety‑critical; in law, the parallel category includes anything that could affect a person’s freedom, immigration status, financial security, public benefits, or professional license. Those use cases merit heightened safeguards: tighter access control, narrower scoping of AI tasks, periodic sampling of outputs for quality, and specific training for the lawyers who use them. Importantly, this is not a “big‑law only” discipline. Solo and small‑firm lawyers can implement proportionate governance with simple written policies, matter‑level notes showing how AI was used, and explicit conversations with clients where appropriate.

Critically, AI does not dilute core professional responsibility. If a generative system inserts fictitious cases into a brief or subtly mischaracterizes a statute, the duty of candor and competence still rests squarely on the attorney who signs the work product. The VA continues to hold clinicians responsible for patient care decisions, even when AI is used as a support tool; the law should be no different. That reality should inform how lawyers describe AI use in engagement letters, how they supervise junior lawyers and staff, and how they respond when AI‑related concerns arise. In some situations, meeting ethical duties may require forthright client communication, corrective filings, and revisions to internal policies.

AI oversight starts at the desk: Lawyers must be able to interrogate model outputs, data quality, and risk signals—before technology impacts patient care.

The practical lesson from the VA’s AI warning is straightforward. The “human touch” in legal technology is not a nostalgic ideal; it is the safety mechanism that makes AI ethically usable at all. Lawyers who embrace AI while investing in governance—policies, training, and oversight calibrated to risk—will be best positioned to align with the ABA’s evolving guidance, satisfy courts and regulators, and preserve hard‑earned client trust. Those who treat AI as a magic upgrade and skip the hard work of oversight are, knowingly or not, accepting that their clients may become the test cases that reveal where the system fails. In a profession grounded in judgment, the real innovation is not adopting AI; it is designing a practice where human judgment still has the final word.

MTC