MTC: Are Lawyers Really Ready for a Wallet‑Free Future? Digital Wallets, ABA Ethics, and the Reality of Going Fully Cashless 💳⚖️

/Tech-savvy lawyers should not leave their physical wallets at home, BUT YOU CAN PROBABLY pare THEM down some.

When previous podcast guest David Sparks over at MacSparky shared his recent post about accidentally going out without his physical wallet—and still making it through the day just fine on his iPhone and Apple Wallet—it captured a quiet shift many of us in the legal profession are grappling with. He walked into his appointment armed only with a digital ID, digital insurance card, and Apple Pay, and everything worked. For a growing number of professionals, that is the new normal. The question for lawyers is more specific: not can we go wallet‑free, but should we—ethically, practically, and professionally—given our obligations under the ABA Model Rules?

Digital wallets are no longer niche tools reserved for tech enthusiasts. Apple Wallet and similar platforms have matured into robust ecosystems that can store payment cards, IDs, insurance cards, transit passes, and even car keys. They sit at the intersection of convenience, security, and risk. As attorneys, we have to examine that intersection with greater rigor than the average consumer, because our technology choices are framed by duties of competence, confidentiality, and client service.

The promise of a wallet‑free practice

On paper, the case for a full digital wallet is compelling. Digital payments can reduce friction at the courthouse café, client lunches, and bar events. Digital IDs eliminate worries about misplacing a physical card. Many platforms add layers of biometric security that traditional wallets can’t match. David notes that Apple Wallet has “been quietly getting better for years,” allowing storage of physical card numbers behind Face ID and making peer‑to‑peer payments a tap‑away. For a solo or small‑firm lawyer, that friction reduction compounds over time into real efficiency.

From a malpractice‑avoidance standpoint, a digital wallet can be safer than a billfold. Losing a traditional wallet means scrambling to cancel credit cards, monitoring for identity theft, and possibly dealing with unauthorized use of your bar ID or access cards. A lost phone, by contrast, can be located, remotely wiped, or locked with strong authentication. Properly configured, it can reduce risk rather than increase it.

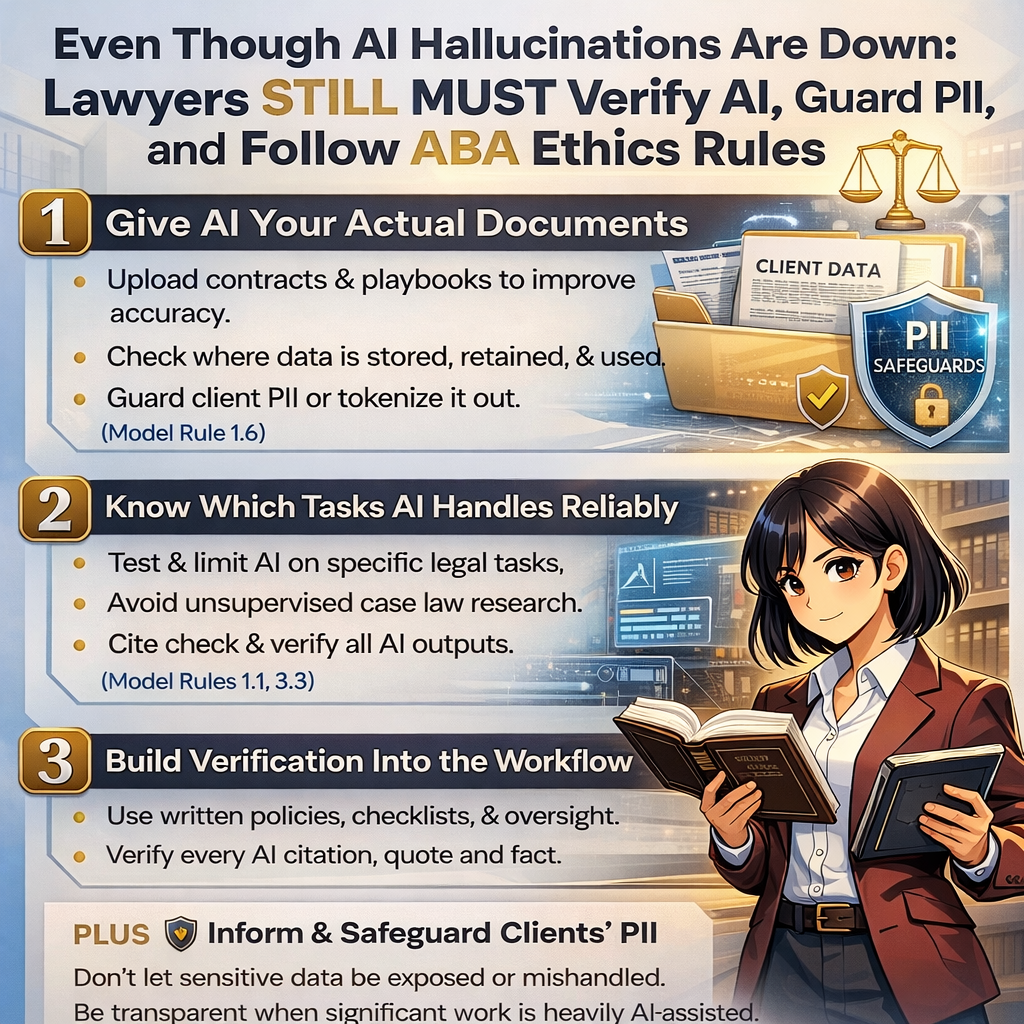

This is where ABA Model Rule 1.1 on competence, particularly Comment 8, becomes relevant. The Comment notes that competent representation includes understanding “the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.” A digital wallet is very much “relevant technology” for a modern practitioner. Choosing not to understand or use it, especially when it offers better security and traceability than analog methods, may itself become a competence question as the bar’s expectations evolve.

The gaps: cash, IDs, and access to justice

There are plenty of reasons not to go “cashless” when leaving home or the office.

Still, David’s hesitation—“there’s a part of me that still feels compelled to carry a small wallet with my driver’s license in it”—should resonate with lawyers. There are pockets of our professional lives where the ecosystem is not ready, and those pockets matter.

First, cash. Many lawyers still tip courthouse staff, parking attendants, baristas near the courthouse, and others in cash—including, in my case, using $2 bills (yes, they are still produced, still accepted, and can be obtained at many banks across the U.S. [At least as of the time of this posting]. I almost always get an excited smile when I tip my barista for his/her work with a $2 bill). Cash remains the lowest‑friction, most universally accepted “protocol” for small-scale human interactions. Refusing to carry any cash at all can put you in awkward social and professional situations, especially in older courthouses or local establishments that either do not take cards or resent micro‑transactions by card. For those committed to cash tipping as a personal or professional habit, a purely digital wallet is not yet a substitute.

Second, physical IDs. While TSA and some states are piloting and accepting digital IDs, acceptance is not universal, and the rules are in flux. David notes he has a state digital ID that “shows up nicely” in Apple Wallet. That is great—until you encounter an agency, judge, clerk, or officer who simply will not accept it. Not all jurisdictions recognize mobile driver’s licenses or digital IDs, and some procedures (e.g., certain filings or in‑person notarizations) still presume a physical, inspectable card. The risk is not hypothetical: show up with the wrong form of ID for a flight or a court security checkpoint, and you may face delay, additional fees, or outright denial of entry.

FROM TSA WEBSITE - “If you are unable to provide the required acceptable ID, such as a passport or REAL ID, you can pay a $45 fee to use TSA ConfirmID. TSA will then attempt to verify your identity so you can go through security; however, there is no guarantee TSA can do so.”

✈️ 🌎 ‼️

FROM TSA WEBSITE - “If you are unable to provide the required acceptable ID, such as a passport or REAL ID, you can pay a $45 fee to use TSA ConfirmID. TSA will then attempt to verify your identity so you can go through security; however, there is no guarantee TSA can do so.” ✈️ 🌎 ‼️

For lawyers, this is not just an inconvenience—it is a competence and diligence issue under Model Rules 1.1 and 1.3. If your failure to carry an accepted ID means you miss a hearing, delay a filing, or cannot visit a client, you have a professional problem, not just a tech annoyance. Likewise, local court rules and security policies may require a specific bar card or government‑issued ID to enter restricted areas. A digital ID on your phone will not help if the sheriff’s deputy at the door has not been trained or authorized to accept it.

Third, connectivity. A digital wallet that is fully dependent on live internet access is a fragile tool in old courthouses with thick stone walls, in rural jurisdictions, or during emergencies. Many modern digital wallets do allow offline transactions at NFC terminals using stored tokens, but not all. If your payment method, ID, or membership pass depends on a cloud verification step and you are in a dead zone—or your battery dies—you effectively have no wallet. Lawyers who rely on public transit, rideshares, or mobile office setups need to consider this in contingency planning, particularly when punctuality is essential.

Digital wallets and legal ethics

From an ethics perspective, digital wallets intersect with several core duties.

Under Model Rule 1.6, protecting client confidentiality extends to how you pay for and manage client‑related expenses. If you are using peer‑to‑peer payment apps or storing client‑related account details in a digital wallet, you must understand their privacy and data‑sharing practices. Some services expose transaction histories, social feeds, or metadata that could inadvertently reveal client relationships or matter details. Configuring strict privacy settings and separating personal from firm accounts is not optional; it is part of your duty of confidentiality.

Model Rule 1.15 on safekeeping property also comes into play if you ever use digital tools to handle client funds, reimbursements, or settlement distributions. While most bars still require traditional trust accounts and closely regulate payment processors, the trend toward digital payments will continue. Using any digital payment or wallet solution around client funds requires careful vetting, written policies, and—ideally—consultation with your malpractice carrier and bar ethics guidance.

Finally, Model Rule 5.3 on responsibilities regarding nonlawyer assistance extends to IT providers and wallet platforms. If your firm relies on third‑party providers to manage mobile device management (MDM), security, or payment integrations, you must make reasonable efforts to ensure their conduct aligns with your professional obligations. Managing digital wallets on firm‑owned or BYOD devices should be governed by a clear policy that addresses encryption, remote wipe, lock‑screen settings, and acceptable use.

Practical guidance: a hybrid, not a cliff

As advanced as our digital wallets are, the legal professional should carry a combination of digital and physical identification, means of payment, and cash!

Given these realities, are we “truly there” yet for lawyers to go fully wallet‑free? Not quite. For most practitioners, the prudent path is a hybrid approach:

Carry a slim physical wallet with a government‑issued ID, bar card (if used locally), a minimal backup payment card, and a small amount of cash for tipping and edge cases.

Use a digital wallet as your primary payment and convenience layer, especially in environments where it is well‑supported and secure.

Confirm, in advance, what IDs your courthouse, correctional facilities, and agencies accept, and do not assume your digital ID will suffice.

Harden your digital wallet: enable strong biometrics, ensure a reputable MDM or security solution manages any firm devices, and separate personal from professional payment flows where possible.

This hybrid approach aligns with Model Rule 1.1’s requirement to understand and responsibly adopt relevant technology while honoring the practical demands of courtroom work and client service. It allows you to benefit from the security and efficiency of digital wallets without betting your professional obligations on the most fragile parts of the ecosystem: universal acceptance and ubiquitous connectivity.

David ends his reflection by asking whether he will ever “truly go out knowingly wallet‑free” and whether he is alone in his hesitation. Lawyers should feel no pressure to be first in line to abandon physical wallets entirely. Our job is to advocate, counsel, and appear—on time, properly identified, and fully prepared. That may mean, for the foreseeable future, living comfortably in both worlds: with a well‑tuned digital wallet in your hand and a minimal, carefully curated physical wallet in your pocket.

MTC