Everyday devices can capture extraordinary evidence, but the same tools can also manufacture convincing fakes. 🎥⚖️ In this episode, we unpack our February 9, 2026, editorial on how courts are punishing fake digital and AI-generated evidence, then translate the risk into practical guidance for lawyers and legal teams.

You’ll hear why judges are treating authenticity as a frontline issue, what ethical duties get triggered when AI touches evidence or briefing, and how a simple “authenticity playbook” can help you avoid career-ending mistakes. ✅

00:00:00 – Preview: From digital discovery to digital deception, and the question of what happens when your “star witness” is actually a hallucination or deepfake 🚨

00:00:20 – Introducing the editorial “Everyday Tech, Extraordinary Evidence Again: How Courts Are Punishing Fake Digital and AI Data.” 📄

00:00:40 – Welcome to the Tech-Savvy Lawyer.Page Labs Initiative and this AI Deep Dive Roundtable 🎙️

00:01:00 – Framing the episode: flipping last month’s optimism about smartphones, dash cams, and wearables as case-winning “silent witnesses” to their dark mirror—AI-fabricated evidence 🌗

00:01:30 – How everyday devices and AI tools can both supercharge litigation strategy and become ethical landmines under the ABA Model Rules ⚖️

00:02:00 – Panel discussion opens: revisiting last month’s “Everyday Tech, Extraordinary Evidence” AI bonus and the optimism around smartphone, smartwatch, and dash cam data as unbiased proof 📱⌚🚗

00:02:30 – Remembering cases like the Minnesota shooting and why these devices were framed as “ultimate witnesses” if the data is preserved quickly enough 🕒

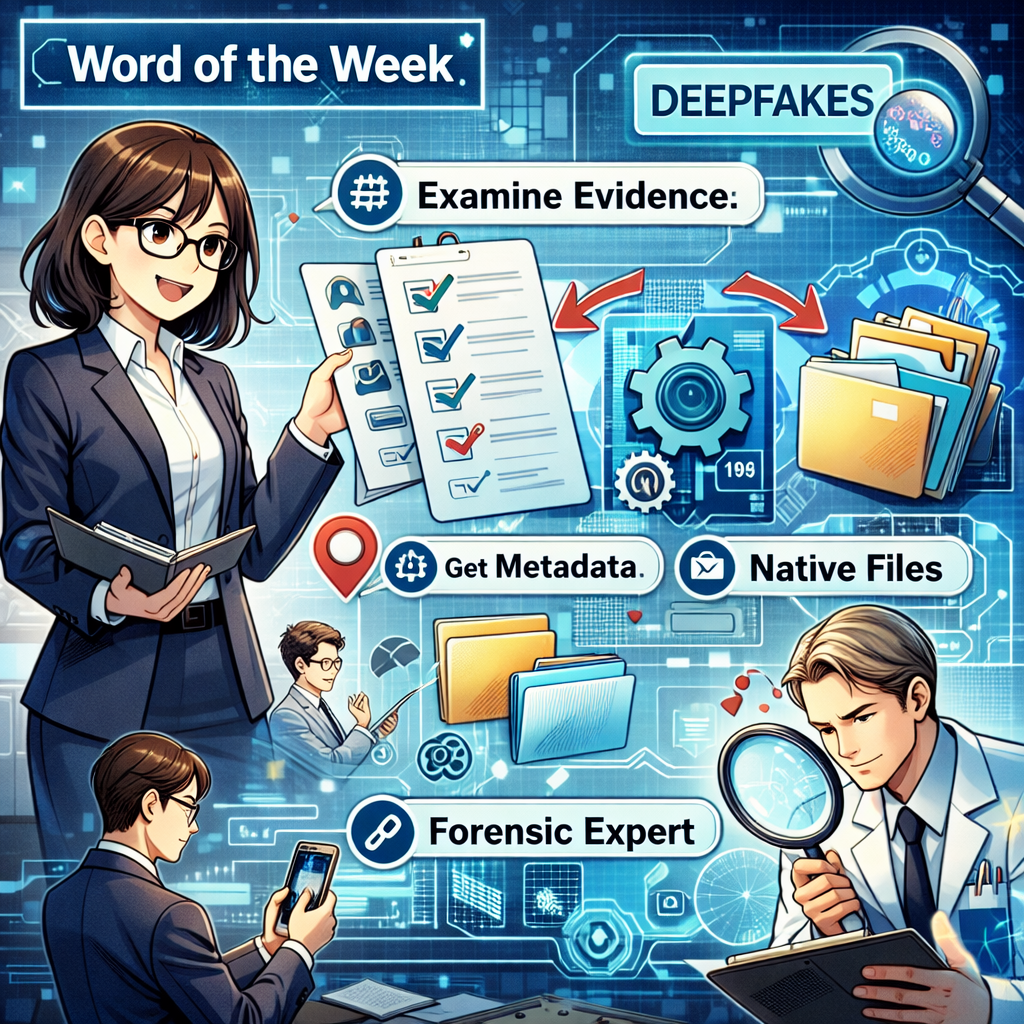

00:03:00 – The pivot: same tools, new threats—moving from digital discovery to digital deception as deepfakes and hallucinations enter the evidentiary record 🤖

00:03:30 – Setting the “mission” for the episode: examining how courts are reacting to AI-generated “slop” and deepfakes, with an increasingly aggressive posture toward sanctions 💣

00:04:00 – Why courts are on high alert: the “democratization of deception,” falling costs of convincing video fakes, and the collapse of the old presumption that “pictures don’t lie” 🎬

00:04:30 – Everyday scrutiny: judges now start with “Where did this come from?” and demand details on who created the file, how it was handled, and what the metadata shows 🔍

00:05:00 – Metadata explained as the “data about the data”—timestamps, software history, edit traces—and how it reveals possible AI manipulation 🧬

00:06:00 – Entering the “sanction phase”: why we are beyond warnings and into real penalties for mishandling or fabricating digital and AI evidence 🚫

00:06:30 – Horror Story #1 (Mendon v. Cushman & Wakefield, Cal. Super. Ct. 2025): plaintiffs submit videos, photos, and screenshots later determined to be deepfakes created or altered with generative AI 🧨

00:07:00 – Judge Victoria Kakowski’s response: finding that the deepfakes undermined the integrity of judicial proceedings and imposing terminating sanctions—“death penalty” for the lawsuit ⚖️

00:07:30 – How a single deepfake “poisons the well,” destroying the court’s trust in all of a party’s submissions and forfeiting their right to the court’s time 💥

00:08:00 – Horror Story #2 (S.D.N.Y. 2023): the New York “hallucinating lawyer” case where six imaginary cases generated by ChatGPT were filed without verification 📚

00:08:30 – Rule 11 sanctions and humiliation: Judge Castel’s order, monetary penalty, and the requirement to send apology letters to real judges whose names were misused ✉️

00:09:00 – California follow-on: appellate lawyer Amir Mustaf files an appeal brief with 21 fake citations, triggering a 10,000-dollar sanction and a finding that he did not read or verify his own filing 💸

00:09:30 – Courts’ reasoning: outsourcing your job to an AI tool is not just being wrong—it is wasting judicial resources and taxpayer money 🧾

00:10:00 – Do we need new laws? Why Michael argues that existing ABA Model Rules already provide the safety rails; the task is to apply them to AI and digital evidence, not to reinvent them 🧩

00:10:20 – Rule 1.1 (competence): why “I’m not a tech person” is no longer a viable excuse if you use AI to enhance video or draft briefs without understanding or verifying the output 🧠

00:11:00 – Rule 1.6 (confidentiality): the ethical minefield of uploading client dash cam video or wearable medical data to consumer-grade AI tools and risking privilege leakage ☁️

00:11:30 – Training risk: how client data can end up in model training sets and why “quick AI summaries” can inadvertently expose secrets 🔐

00:12:00 – Rules 3.3 and 4.1 (candor and truthfulness): presenting AI-altered media as original or failing to verify AI output can now be treated as misrepresentation 🤥

00:12:30 – Rules 5.1–5.3 (supervision): why partners and supervising lawyers remain on the hook for juniors, staff, and vendors who misuse AI—even if they didn’t personally type the prompts 🧑💼

00:13:00 – Authenticity Playbook, Step 1: mindset shift—never treat AI as a “silent co-counsel”; instead, treat it like a very eager, very inexperienced, slightly drunk intern who always needs checking 🍷🤖

00:13:30 – Authenticity Playbook, Step 2: preserve the original and disclose any AI enhancement; build a clean chain of custody while staying transparent about edits 🎞️

00:14:00 – Authenticity Playbook, Step 3: using forensic vendors as authenticity firewalls—experts who can certify that metadata and visual cues show no AI manipulation 🛡️

00:14:30 – Authenticity Playbook, Step 4: “train with fear” by showing your team real orders, sanctions, and public shaming rather than relying on abstract ethics lectures ⚠️

00:15:00 – Authenticity Playbook, Step 5: documenting verification steps—logging files, tools, and checks so you can demonstrate good faith if a judge questions your evidence 📝

00:16:00 – Bigger picture: the era of easy, unchallenged digital evidence is over; mishandled tech can now produce “extraordinary sanctions” instead of extraordinary evidence 🧭

00:16:30 – Authenticity as “the moral center of digital advocacy”: if you cannot vouch for your digital evidence, you are failing in your role as an advocate 🏛️

00:17:00 – Future risk: as deepfakes become perfect and nearly impossible to detect with the naked eye, forensic expertise may become a prerequisite for trusting any digital evidence 🔬

00:17:30 – “Does truth get a price tag?”—whether justice becomes a luxury product if only wealthy parties can afford authenticity firewalls and expert validation 💼

00:18:00 – Closing reflections: fake evidence, real consequences, and the call to verify sources and check metadata before you file ✅

00:18:30 – Closing: invitation to visit Tech-Savvy Lawyer.Page for the full editorial, resources, and to like, subscribe, and share with colleagues who need to stay ahead of legal tech innovation 🌐